Sansa Stark is a Strong Female Character

There will be book and television spoilers in this article. Reader’s discretion is advised.

A little while ago, when I first started reading George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, the books which the Game of Thrones television show is based from, I started thinking about the female characters of Westeros. I thought about what cultural practices and processes shaped them and influenced their minds into the different personalities that we as readers and as an audience get to see.

Lately my friends have been talking about Sansa Stark: particularly motivated by Julianne Ross’ article Why Sansa Stark is the Strongest Character on ‘Game of Thrones.’ Ross makes a point of stating that she is focusing on the character in the television series and not how she is portrayed in the books. She specifically goes into how even though Sansa identifies more with the traditional idea of the feminine, of the courtly lady, how she is no less a hero in doing so.

Sansa Stark is one of those characters that also receives a considerable amount of contempt: being seen as spoiled, weak, cowardly, or even treacherous but more than certainly naive.

I will admit that when I first read A Song of Ice and Fire, I didn’t particularly like Sansa. She came off as spoiled, arrogant, and downright ignorant and selfish. But then I looked at where she came from. In fact, I looked at where she and other women came from. If you watch the television show or, more specifically, read the books you begin realize that while Westeros seems to be an awful place for anyone to live, it is particularly bad for women. You have this setting, this social structure from Westeros to Essos where rape seems to be a given act in the many wars that are constantly going on. And these are for the smallfolk women.

In Westeros, the women of the nobility or the various Houses seem to have a better existence. They are taught how to read and write. They are generally protected as they grow up and they have the guidance of various mentors and a good name to back them up. Of course, there is the patriarchy of the entire thing. When it all comes down, highborn women in Westeros marry whomever their fathers say they will marry. They are little more than dowries, breeders, and bargaining chips exchanged between the Houses in an arrangement that is otherwise part of the political bandying known as “the game of thrones.”

Now, some of these highborn women learn how to use the traditional feminine role to their advantage. They hold court and meet with their friends. They organize social settings, or they make themselves popular within these settings. Some begin to understand that power is not merely a sword or an army or even a drop of poison, but information and the right word whispered to the right or wrong ear. The point I’m trying to make here is that those women who understand how to use what is traditionally considered feminine in Westeros and are capable blending into that role, do so in order to survive and thrive in an environment that they can navigate or even subvert. This is, of course, not always the case. Arya Stark’s interests are more in line with the smallfolk, the commoners of Westeros, and martial considerations whereas Brienne of Tarth doesn’t have what many consider to be traditional “feminine traits” and prefers the straightforward and “masculine-gendered” idea of chivalry and battle prowess.

And as Ross in her article states, audiences generally seem to consider these kinds of female characters as stronger and more heroic. However, heroism is a questionable word at best. Throughout our own history, and that of Westeros, heroism has been applied to people who have done morally questionable and even reprehensible acts. And sometimes heroism glorifies a certain kind of suffering or struggle that is, really, in the end all about survival. Someone can be in a terrible place and have to act a certain way in order to keep on living or maintain their sense of sanity because–in the end–they have no choice.

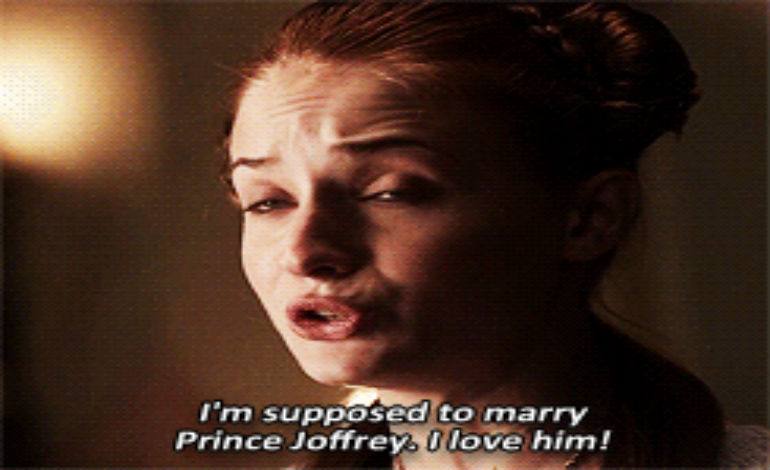

Sansa Stark, at this point in the television series, would not consider herself a hero and right now, she too and despite her adherence to a more conventional archetype of femininity, has no place in courtly intrigue. Right now, Sansa Stark is a child. Sansa is a girl who has been sheltered by her lord father in Winterfell and kept from seeing the worst of humanity. She doesn’t hate her servants and she even has a friend in the form of Jeyne Poole her father’s Steward’s daughter. But she has been raised with stories of courtly love, nobility and true knights. She is the girl that always wanted to meet her Prince Charming and ride off with him. Her instructors and her mother Catelyn in particular train her to be the “perfect young lady.” In fact, Sansa really has no idea about politics or the game of thrones and what is done to maintain power.

She is a girl that takes her world for granted, and the illusions behind it even more so and when she gets to King’s Landing she has that veil slowly ripped off of her. Here is a girl whose childhood wolf pet Lady gets slaughtered because another wolf attacked Joffrey. Here is a girl who looks up to the beautiful Queen Cersei as something of a fairy-tale surrogate mother before she knows how dysfunctional and shallow and cruel she truly is. Here is a girl who finds her beloved prince and learns the hard way that not all princes are noble and kind.

Here is a girl who is coerced into betraying her own father for political games she has no understanding of, who watches her father get executed, who has to look at his decapitated head and gets beaten by knights for the King–her former beloved’s–amusement.

She is married into the House that ends up instigating the slaughter of most of her family and to a man she doesn’t love.

Here is a girl who likes tales of maidens and true knights and lemon cakes.

And Sansa gets used. And used again. And again. She ends up getting her first menstrual cycle, which her mother should have been there to talk her through, and has to share that with Cersei: all the while dreading that natural human function because of what it will mean for her value as a woman, as a breeder, in this situation. That one scene sticks out at me the most and if everything else wasn’t enough to make Sansa grow up in such a traumatic way, that symbolized it the best from my perspective.

Even so, she still believes in those tales her mother and tutors used to tell her. But more than that, Sansa actually cannot stand to look at cruelty and even pleads for Ser Dontos’ life when he arrives drunk to one of Joffrey’s celebrations and when she tells Margaery Tyrell of Joffrey’s true nature. An even greater example of Sansa’s moral nobility is when, during Stannis Baratheon’s siege of King’s Landing and Cersei’s descent into despair, she actually leads the women hidden away in the castle in prayer: keeping up morale and hope while their Queen essentially fails them and feels sorry for herself. The fact is, there is still that honour and decency that her father and House Stark instilled in her as well her own sense of compassion.

She is a girl who hasn’t been warped by bitterness and shallow displays of power like Cersei or her aunt Lysa Arryn, or blinded by the idea that political power will always benefit family first like her mother Catelyn (which was far more pronounced in the books where she wanted Lord Eddard Stark to go to King’s Landing as Hand), and she is definitely not as shrewd or as clever as Lady Olenna Tyrell but again, she found herself in this entire situation as a child. And now, for better or worse, Sansa is growing up: and she is learning. She is learning the rules of how to survive in her suddenly very cruel world.

I won’t say very much more about Sansa’s journey, but I will tell you this much. She may not be a warrior like Brienne, or a rebel like Arya, or even the fierce woman that Daenerys Targaryen forced herself to be by necessity but Sansa has many strengths that already exist inside her: great intelligence, a growing knowledge of the court and its rules, as well as compassion. I suspect she might become more ruthless in some ways, but never callow or vain or arbitrarily cruel. She won’t be as direct in her lessons of power, but she will do what she has to and, if she can, maintain her integrity and capacity for empathy in doing so. And, more than this Sansa Stark has also demonstrated, through her morality, the ability to take charge and provide a deep sense of moral support, inspiration and hope: as some might think that a good queen should.

In the end, I don’t think that Sansa Stark is a hero, or a coward, or a weakling. I think that she has her own personality and will eventually find her way through the game of thrones. I think, by necessity, she will continue to be a strong female character: perhaps not the strongest, but definitely one of them.