Bitch Planet is Non-Compliant

If you are a comics geek and you haven’t been reading writer Kelly Sue DeConnick’s and artist co-creator Valentine De Landro’s Bitch Planet, you should be.

My first impression of Bitch Planet, from what I saw of Issue #1 was that it would be a comic not unlike something Pat Mills would make: something gritty with major punk themes that, in particular, would parody an established comics trope or convention. Even more so, I was expecting a highly political grindhouse death battle situation where the characters would screaming “Fuck the Man!” in literal cage grudge matches when not engaging in gang wars or creating anarchist havens for one another.

Of course what I found was something that — while it plays with those themes — is entirely different. I suppose anyone who is part of the Carol Corps would have been able to tell me that. This was before I’d actually started reading Kelly Sue’s Captain Marvel run and while I saw the great potential in the mythos of Pretty Deadly I had a feeling that Bitch Planet would have a very different story.

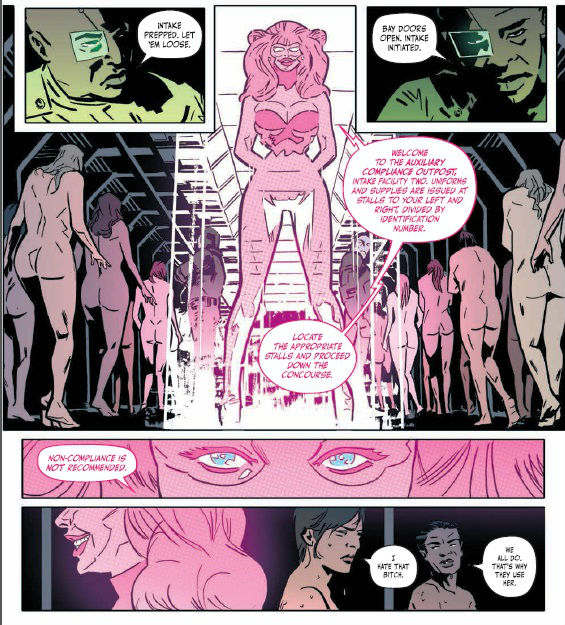

I’ve read that Bitch Planet essentially exploits the exploitation genre: specifically with regards to fictional stories about women in prison. So picture the following scenario. Imagine you are in the future. Space travel, surveillance, and holographic technology exists. There is at least one civilization, or national government, that seems to be able to colonize other planets. Everyone is in smart suits and dresses and they get their creature comforts. But crime still exists and there still means, read: prisons, to deal with it. There is one prison planet in particular referred to as the Auxiliary Compliance Outpost.

It is this world that deals with particularly extreme female criminals. Their crimes are numerous: theft, assault and battery, murder, infidelity, abortion, gender treason, hysteria, and a slew of other crimes that — when you get right down to it — are all acts of non-compliance.

I think you can see where this is going. Still, I’m now going to go into some spoiler territory so if you want to read this ongoing comics series and you don’t want to be surprised, or should I say too surprised, you might want to stop here.

The fact is, non-compliance is a very real theme in Bitch Planet: not just within the society of the New Protectorate and its Council of Fathers, but also in how Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro play with the comics series’ women in prison exploitation genre itself.

Issue #1 starts off at a place with a woman attempting to get through a crowd to her job constantly apologizing. This in itself might not mean anything on the surface until you see the transition to where the story is going. It’s pretty clear that the Auxiliary Compliance Outpost, or Bitch Planet as many call it, is a metaphor for that entire society. There are little signs of this in how all of the female characters behave. Even in Issue #3, which is a character origin story, a woman at a bakery goes as far as to tell a particularly obnoxious man that she isn’t rolling her eyes at him. Women’s behaviour is observed and policed in this futuristic setting for a variety of reasons: sometimes to the point of incarceration and “re-education.”

Kelly Sue herself is already tapping into that place of patriarchy where women’s behaviour is expected to be conciliatory and passive with regards to men in society. At the very least, she is bringing to light, through her narrative, these traits that women are still expected on some level to embrace to get along in “polite society.” But the creative team go further with this. Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro depict the guards of Bitch Planet wearing visors not unlike mirrors. Virginia Woolf, in A Room of One’s Own utilizes the metaphor of the mirror: of patriarchy needing women to be an inferior or more coveted reflections of men in order to make them more powerful or heroic.

And in Issue # 3 of Bitch Planet it’s shown that the New Protectorate is attempting to see into the minds of women with something called a cerebral action-potential integration and extrapolation machine. It’s purpose is, apparently, to reveal to a committee of men exactly what a woman’s “ideal self” truly is in order to “help her” reach it. Conveniently the device utilizes a mirror.

And Bitch Planet also uses painfully neon holograms to parody the New Protectorate’s “ideal form” of women: to use them to train, indoctrinate, and punish the prisoners at will: a twisted derivative of advertising turned propaganda to a socially — and now physically — captive female audience.

The mirror visors, the mind device, and the holograms are created to symbolize one very important fact: that women in Bitch Planet should prioritize how others see them over how they see themselves.

And, of course, this is always done for “women’s own good.” The New Protectorate seems to have a very paternalistic view of how to deal with women, and this chauvinistic attitude peters down from the Council of Fathers, to the almost exclusively male-committees making decisions about women’s bodies and minds, and to the common man and woman. Even men, if they are not in certain standing within the hierarchy are, at best, useful tools and at worst underlings to be reminded of their place. And either way, they are just another form of commodity that can be disposed of at will.

The fact that Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro are able to convey the humanity of both oppressors and victims only makes this dynamic even more disturbing.

It is also clear that, unlike H.Y.D.R.A. in Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. it isn’t so much that “compliance will be rewarded.” On the contrary: compliance is expected. And non-compliance will always be punished. And even then, like any good patriarchal model, there is the other side of the same coin: violence. It’s safe to say that beatings are commonplace on Bitch Planet and abuse of power as well. The two male supervisors of Bitch Planet seem to view their prisoners as little more than trite entertainment for their arbitrary attentions, and seem detached from sending guards in to break up riots in any way possible: whether the prisoners are violent or not.

So whether women in Bitch Planet are compliant or not, it almost doesn’t really seem to matter. Their lives are dependent on the whims of men in power and those to whom they give power. Women’s privacy, personal space and sexuality are something to be bartered and compromised. This can be see from Issue #2’s emphasis on a man slapping two waitresses on the buttocks all the way to Issue #4, where there are more unpleasant metaphors abound when the reader finds out there is a hole in the shower areas where two women can be intimate with each other provided that they do so in front of the guard viewing them behind the wall: another metaphor for the male gaze.

There are also some very loaded racial descriptions, body-shaming, and gender terminologies bandied about by those in power: terms that women are expected to accept as commonplace. Bitch Planet shows the reader a patriarchal setting that thrives from “keeping up appearances” and encouraging others to do so: from the guards who hide behind the power of their masked anonymity when doling out violence and violation — perhaps a metaphorical jibe at Internet trolling of women by Kelly Sue and creative company — all the way to using the veneer of events such as funerals, blood sports, and camera smiling to maintain the status quo. And it goes without saying that if this system somehow “makes a mistake,” it will not hesitate to use any means to “correct it” and save face: even if they officially decry state-sponsored murder.

This is the structure of compliance and it is all the more terrifying when you consider that it is only a few steps away from a lot of the attitudes of people in power in our time. Indeed, according to an interaction between the apparent series’ protagonist and one of her jailers, this New Protectorate seems to have developed not too long ago in that world’s future. In fact, the creators could leave this world on its own: as a cautionary tale as to what kind of dystopia might happen if we take our freedoms for granted and let them get legislated out of the way for expediency’s sake or out of fear born from a particular trauma.

But, if there is one thing I’ve learned, Kelly Sue DeConnick does not like to leave these things the way they stand.

The creative team begins with the protagonist. At first, the reader doesn’t know who the main character is going to be or even if there is going to be one. Then the narrative starts to focus on an older white woman named Marian Collins who has apparently been wrongfully imprisoned on Bitch Planet. Kamau Kogo, a Black athletic fighter who, at the moment, seems to be the actual story’s protagonist after starting off as a peripheral or secondary character.

What is even more interesting is that, four issues in, we still don’t know much about Kam or why she is on Bitch Planet. There are clues. In Issue#1 the head prison supervisors actually discuss some of the prisoners and mention the inclusion of one volunteer. Whether or not this person is in the prison program as a inmate or a guard is another story entirely: especially, as by Issue #4, the reader finds out about the existence of an unnamed — an anonymous — prisoner. But what is known is that the protagonist is looking for someone, or something. Only time will tell if these elements will interlap and, at the moment, Kelly Sue is keeping her cards to herself.

Kamau is so bad ass that if V ever approached her the way he did Evey in a hypothetical V For Vendetta / Bitch Planet crossover, she would probably punch him in the face for his troubles.

What we do know is that while Kam comes from one of the most exploited groups in all of history — being a Black female — she is also physically strong, athletic, well-trained and apparently had a career before the establishment of the New Protectorate. And she is extremely smart. For instance, she takes that hole in the shower walls, with its unfortunate dual metaphor of female exploitation and the male gaze, and she smashes through it: making it into a spot on the wall of possibility of which Virginia Woolf may have been proud. The guard behind that hole is brought painfully into the situation. His anonymity and the power behind it is taken from him as she knocks off his helmet: leaving him vulnerable to her as she plans to exploit the system that is exploiting her and her fellow inmates. Essentially, she takes the obligatory shower scene, uses it and destroys it to further her own plans.

In Issue #2 of Bitch Planet, Kam is approached by a special operative with a proposition to create an all-female prisoner sports team to fund the Bureau of the New Protectorate. The sport is called Megaton, or Duemila: a form of Calcio fiorentino: an activity reminiscent of football with the ability to throw punches and kicks. It is a bloodthirsty sport and while there may be “no crying in baseball,” I suspect there might be some dying in Megaton. At the same time, however, the game will give the prisoners a chance to fight an all-male guard team on their own unconventional terms. It will be a publicly viewed game and everyone in the Protectorate and the world will be watching. It is an opportunity to challenge the game: to subvert their own exploitation.

And while I’ve also read that Bitch Planet is considered to be Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale meeting Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds: I would add that it also has some Orange is the New Black, some Battle Royale and a little bit of A League of Their Own for good measure.

So here we have both Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro playing with stereotypes of femininity, or perceptions of it in much the same way that her characters will be exploiting the hell out of their own system. This may be a dystopia, but there is some resistance: even in the very design of the comic itself. I’ve already mentioned that Valentine De Landro’s art in Bitch Planet has a very gritty punk aesthetic. In fact, I can go further and state that it’s reminiscent of the style of drawing found in many comics from the eighties and nineties: complete with stark colours and eerie neons. But it is the series’ usage of the back matter of each issue — each one designed by Laurenn McCubbin — that is truly something to behold. Each one utilizes the aesthetic of an old, pulpy classified page: in which subliminal patriarchal ads are subverted by feminist messages and parody for the discerning reader.

In fact, one of my few regrets about Bitch Planet being collected into trades is that the back matters, the essays from inspired feminist contributors, and the comments sections won’t be included. At the same time, it makes me very thankful that I’ve started to read Bitch Planet in their separate comics issues. For the first time in ages, I can almost understand what it felt like to be a reader collecting an issue of Sandman, V For Vendetta, or Watchmen each month: while eagerly waiting for the next story to come out and somehow feeling involved in some of the process as a reader. Really, I feel like I am somehow a part of watching a masterpiece continue to grow into fruition. To those who say that no one has created an epic stories equally those of Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, or Grant Morrison I would just love to direct their attention to what Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro are doing right now.

So, to end this off, let me just say this. If you like murder mysteries, prison dramas, dystopias, political intrigue, grindhouse violence, human characters, and a feminist story that shows clearly what it is critiquing through clever storytelling and human characters — if you yourself are non-compliant — then come acquaint yourselves with Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro’s Bitch Planet.