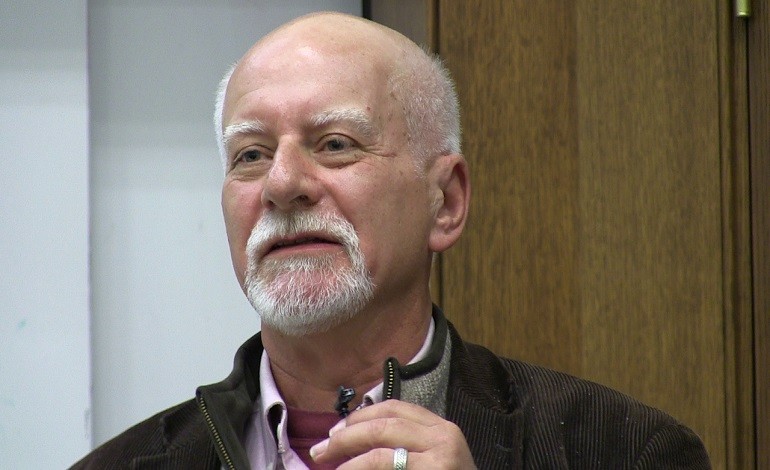

An Hour with Chris Claremont

You know, I’ve spoken with some comic greats before, but none have ever had such a dramatic effect on the history of my comic reading development than Chris Claremont.

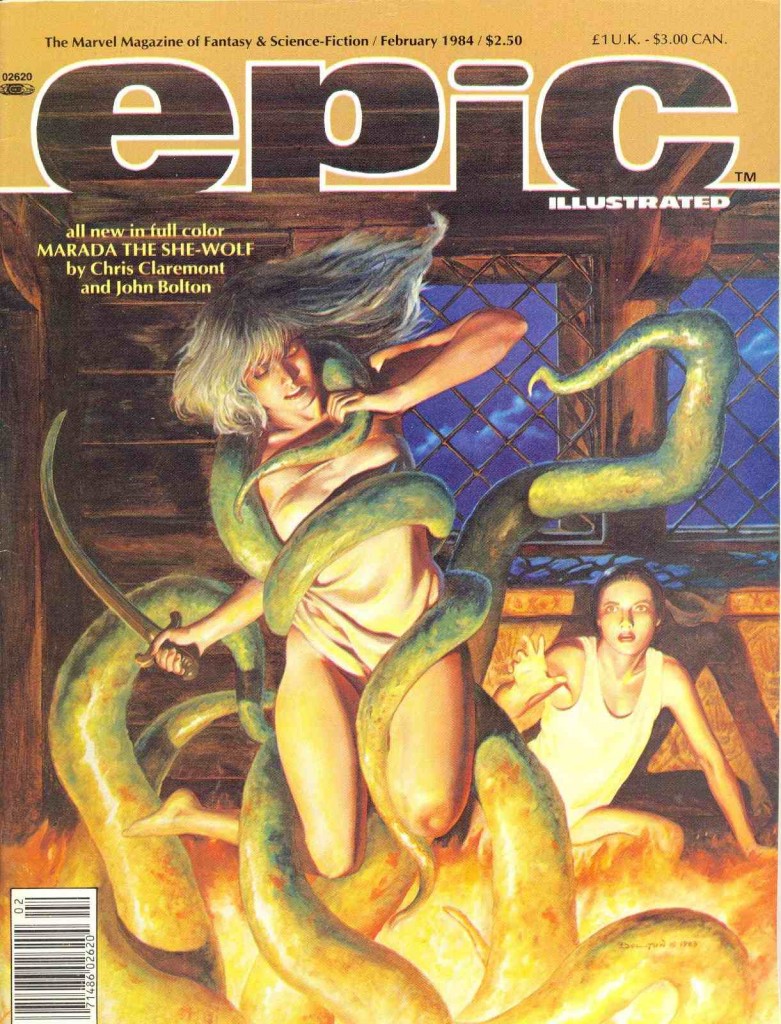

There was a time when most of the regular Marvel titles I picked up in my youth bore his name on the cover. If Claremont wrote it, that was also a deciding factor if I was going to read it or not. Claremont wrote the X-Men for Marvel over 16 years, longer than any other writer, creating iconic characters like Kitty Pryde and Emma Frost and developing memorable stories like The Dark Phoenix Saga with John Byrne or the graphic novel God Loves, Man Kills with Brent Anderson. His creator-owned comic works like Marada the She-Wolf and The Black Dragon, drawn by legendary artist, John Bolton, were also amazing works that are timeless and remain hallmark examples of comic storytelling.

And I had his phone number.

I had a chance to talk to Chris recently and he shared a little about his past endeavours and a bit about his present. It was an amazing hour of insight and a fantastic chance to just listen to a comic legend talk a bit about his career. We started the conversation talking about his collaborative work with artist, John Bolton Marada the She-Wolf and The Black Dragon. Both were stories that were featured in Marvel’s Epic, Illustrated in 1982. We eventually finished off with a bit about the recent work that he had done on Nightcrawler. All in all, it was a great, relaxed conversation about an iconic writer’s experiences.

JKK: Let’s start with talking a little about your work on Epic, Illustrated. When people think of that magazine, your work is included in a stellar line of talent. How does that make you feel?

CC: Umm … Obviously it’s cool to be included in a “stellar line of talent”; on the other hand, what I think is more cool is the quality of work that inspired that and the magazine that brought us all together. I mean, I think the work, for example that John Bolton and I did on Marada and The Black Dragon was exemplary of the kind of quality and I guess, breadth of material Archie Goodwin and Jo Duffy gathered for the magazine. The essence of it was Archie’s attempt, I think, to make it as rich and meaningful a source of comic fiction and material as the best graphic album in Europe and prose anthology magazine in the United States at the time.

JKK: Marada and The Black Dragon stand out as amazing tapestries of work. How did all that come about?

CC: Well, I guess, Marada started out with Ralph Macchio going to England and finding John [Bolton] and getting him started on a Conan – I believe it was a Conan story, for Savage Sword, possibly – you’ll have to ask Ralph or John. It was wonderful that I wandered in and saw the art that John was delivering for the Conan material and I just went “holy cow – this guy is brilliant. I gotta do something.” And what then developed was the two of us, John and I, putting together something that was originally intended as a Red Sonja story. Umm, which would be obviously in the Conan large format magazine. At which point, Marvel, in one of those twists of fate that seemed like a pain in the neck at the time, which in retrospect we applauded with enthusiasm, uh lost the license. So there was John and I with umpty-bump pages of original material – beautiful original material, because John – to say John is a brilliant artist is like saying something obvious like the sun is shining. But we had nowhere to publish it.

JKK: Right.

CC: And so I sat down with Jim Shooter to see if we could figure out what could be done. An idea was floating around in the back of my head to the effect of since we had the whole idea behind the story itself, in sort of parallel to other work I was doing at Marvel at the time was designed to present the character in a way that we had never seen before, severed from the traditional presentation. I could, in my case, for example, I couldn’t figure out how she could go through her whole life in an armoured bikini, so I wanted to – especially when you’re dealing with an artist of John’s calibre – get her a different set of costumes. So the character didn’t look like Sonja in the bulk of the story and the way I was pitching it to Jim was why don’t we just change it? Could it be within Marvel’s purview to let John and me buy back the pages and sell them to Archie Goodwin for Epic? And Jim being Jim finished the idea before I got five words into it.

JKK: That’s amazing.

CC: No … it turned out that he had already talked to Archie and pretty much thought that this would be a great – a really cool thing. And what was even better was all that Jim asked, or what was required from his perspective of being editor-in-chief was that they just re-applied the cheques; instead of billing it to Red Sonja – which didn’t exist anymore – it was billed to Epic. So it was a remarkably generous and equitable arrangement all around.

JKK: You know that’s interesting. When I spoke with Jo Duffy, she had remarked that Jim Shooter should be credited with the decision in putting you all together and giving the rights to Marada to you.

CC: You know, the frustration in working with Jim was that he could be the best of bosses and the worst of bosses often simultaneously. He had so many instincts that were so generous and so spot on in terms of helping creators build an equitable life for themselves and a professional relationship with the company. And yet at the same time, he could, and for him, the best and justifiable of reasons, do things that would make you want to kick him.

JKK: (Laughs) That’s hilarious!

CC: I mean, you know, the thing with Jim, it was hard for him to seek and hold allies. And so, at the end, when push came to shove, he managed to somehow piss off everybody. And you know, uh, that was the way it went.

JKK: In counterpoint to that, what was it like working with Archie Goodwin?

CC: (Deep Breath) He was … the best. He was the best. You know, one of the best people, the best writers, the best editors. Much like Stan, there was little he couldn’t do that he couldn’t do better than anybody. And he was a remarkably decent, nice guy. So you couldn’t argue with him even when he was wrong, because nine times out of ten he wasn’t, and he was so charming about it that you were just knocked off your feet.

JKK: Were there any particular anecdotes that stand out in your mind when working with Archie?

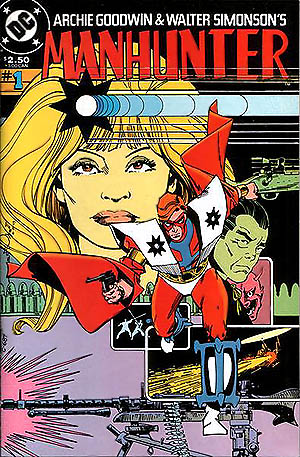

CC: Hmmm … well, I hate to say this, it’s so far back that I’m not entirely confident in trusting my memory. I mean, one of the things that always drove me crazy was that he got to play with Simonson so many times that the rest of us didn’t! (chuckles) Oh what was the DC story … it was his and Walter’s? I can see the images but I can’t think of it …

JKK: Manhunter?

CC: Manhunter. That was it. Thank you.

JKK: (Chuckles) No problem!

CC: What was marvelous was that Walter [Simonson] had the breadth of storytelling ability to take Archie’s instincts and translate them into the actual panel structure, but the key also was that you had Archie’s [thumbnail] guide there in front of you and you could see it was all there for Walter to draw from. And you know it was just incredible – just wonderful and the text was a superb compliment to the visual structure. That’s the kind of thing I would assume I would see in Walter’s class if I were teaching a writing course … you would have to find a way to express the story in visual terms and present it to an artist in a way that would enable the artist to bring it to life visually. And Archie, with Walter on Manhunter, he had it. He had it with Walter on Manhunter, [John] Buscema on Wolverine, or whatever, it was just absolutely wonderful. Then of course, you know, I feel smug in a way because Archie’s first story for Marvel, I think, was an issue of Hulk way back in 1973 was one off of my plot: the return of Jarella – oh God, I can’t believe I’m remembering this, but it was wonderful!

JKK: I want to talk a little about the process of Marada and The Black Dragon. What was it like working with John Bolton?

CC: (Pause) Magnificent and infuriating. Magnificent, because whatever I asked him, he could draw superbly well and often come up with a better way of presenting it than any idea I had of. Infuriating, because I think, like every halfway decent comic book writer, when you see a talent that profound and a skill that extraordinary, you just want to hold onto it forever – and John insisted on going off and working with other people (laughs) and doing other stories and, you know … darn! And then you see the other stories and you say “shoot, I wish I’d thought of that!” (laughs)

JKK: Right … right!

CC: You know, whether he’s working with Annie Nocenti or the half-dozen other guys he’s worked with over on Epic … umm, the thing with John is that I could ask him for anything, whether it was Marada, Black Dragon or X-Men; he could not only do it in a style that was uniquely his, but also in a way that brought visions to life. I mean, if you flip through Marada…

JKK: I have it right in front of me.

CC: It was my first graphic novel. The story in Africa, and then the Arab adventure where they’re running for their lives – the people that you meet along the way, the character … the scenes in the Africa adventure where she and um …

JKK: Arionrhod?

CC: Arionrohd … are out in the middle of nowhere and, you know, basically wearing nothing but a t-shirt and running for their lives and yet he in a matter of panels gives you this presentation of the people, the space, the situation; the fact that at the beginning of the story – ah, poor Marada, this happened to her a lot: Marada looked like she’s been run over by a bus! After the fight on the hill, and then of course, Arionrohd fixes it, but it’s just the evocation of the society of … the African society that was distinctly different from the Roman society she’s from … or the last story, where she finds herself working with a pirate king and they’re sitting in a bar and he’s a charming wretch! And that was Sergio Leone – they’re running and jumping and having a great fight, kicking the dickens out of all the bad guys, and suddenly: mmph! The poor pirate gets skewered!

JKK: (Chuckles) That’s right.

CC: Dang. But my deep passionate regret with John is that, you know, for better or for worse, is that when I start playing a character or a story type, it’s generally a big story, and for me, there are chapters that are left untold: Marada and Arionrhod getting back to Rome – home. And the reader and the writer in me have always been yearning to see John’s evocation of Rome at the turn of the 1st millennium, where Augustus has just come to power; where Marada has returned to the city of her mother’s birth – the grand-daughter of Julius – the one person you don’t want to be at that time! All of the intrigue that is going on between the succession to Augustus, leading up to Tiberius and then Caligula. And I’m sitting there in my head and asking how could we evoke the coliseum? How could we make Russell Crowe look like a chump? There’s a sense of how can we make a spectacle … how can you take one part Charlton Heston riding his chariot and one part Russell Crowe and throw it all together and then pot it with something uniquely Marada?

JKK: Right and then a little bit of sorcery thrown in for good measure.

CC: Ah, you know, why spoil the beauty of a thing with subtlety? (Chuckles) Just lay it on with a trowel. (Sighs) The stars just haven’t aligned themselves properly unfortunately. We’ll just have to keep our finger crossed. The thing with John that has always made him so wonderful as a storyteller is that you could do something as prosaic as the story I did for X-Men where it’s basically the tale of a writer with a writer’s block. And then four pages in he meets Ororo and things get silly. Or you could, you know, I mean, do total surreal fantasy. You could do science fiction; you could do history, as in The Black Dragon or fantasy history, like Marada. You could toss anything John’s way and he would swirl it around and give it back to you his way that managed to be utterly true to the story’s logical structure of scenes and yet uniquely him.

JKK: Yeah … I remember the characters he drew to be amazingly true to life. You could actually imagine this person as real because they seemed familiar.

CC: John would make real visualizations. He would find real skeletal structures, real features, real visualizations. You would look at a character on a page and think: that’s cool. I’ve seen someone like that. And throw in crackerjack storytelling. You know, it’s … you know, here’s a moment: in the first chapter of Marada. When she’s rescued and taken up north [to Donal’s castle]. She wakes from her own nightmare. Donal comes in and then Arionrhod comes in … and there’s this itty-bitty panel – in a multi-panel page. She’s standing in a doorway – she’s like this 10 year-old little girl, and she’s rubbing her eyes like she’s just woken up and I just realized, holy cow! Not only is she rubbing her eyes, but she’s pigeon-toed! And … to me, as a reader and a writer, I look at that and think: Oh my God. That’s wonderful! It is a real moment. Anybody who has been twelve or has a daughter who was twelve can look at that and say: holy cow! I’ve seen someone in that pose. That’s a pose from life! And to me that takes on what everyone is used to thinking, well, it’s fantasy; it should be women with big hooters and guys with big guy hooters. It’s all cliché, but this is a moment of realism. If you look at this girl and think she reminds me of a real person – she might be a real person. Then the events of the story can be that ever more real.

JKK: Yes! Exactly! That was what I was thinking looking at that scene for the first time. It was like I knew this girl.

CC: Mmm-hmm. If you look at the way he outfits Marada, when she takes off her cloak and is about to beam down to the nether-world. You know, he sat back and figured out, okay, what is she going to look like when she goes into battle in this time, in this reality? The sword, the shield has weight. Her clothes have detail. When you’re working with an artist of that calibre, that’s what you get. That’s why he is justifiably unique and totally deserved of the praise. He gives you something that no-one else does and makes you want to see more.

JKK: Let’s switch to some of your more recent projects. What was the draw to work on Nightcrawler?

CC: It was a lot of fun!

JKK: And what was it like to work with Todd Nauck?

CC: Superb! A distinctive visual style and a total understanding of the character. And … a willingness to try the craziest of ideas I threw at him from all directions. Essentially, in the last two issues, it was just like – I was trying to figure out how to convey to the reader the fact that Kurt and company were surrounded by thousands of odd-looking kids, for whom they are trying to rescue. And in presenting them, by giving the audience a visual sense of who, uh, what’s at stake, making it that much easier to the reader to identify with the kids as the victims and Kurt, and his determination as the hero. And of course, the utter villainy of the bad guys. And he pulled it off. So, kudos galore to Todd.

JKK: There was no-one happier than me to see you return to an X-Men title. So how do you reconcile the storyline of Nightcrawler to the various convoluted storylines of all the other X-Men storylines out there?

CC: I have no idea. You know, basically I sat down with the editor … and I pitched the ideas; I did the stories. Ideally, I would have preferred the series to be an ongoing one and for it to have lasted longer, but it wasn’t in the cards. Um, you know, I think the difference between the company today and the company, even twenty years ago, let alone forty, is that it’s a much more specifically structured storytelling environment. There is a very definite intent for what is being presented and how it’s being presented – it’s building to a sequence of grand events which will culminate in revelations that will have yada-yada –blah-blah-blah and ideally inspire more great stories. But the thing is, that the direction – it’s got a very specific direction and it’s very challenging for a single writer no matter who they are to step in on any character who might be considered of necessity a peripheral character in the overall scheme of things – on a peripheral title in the overall scheme of things and try to make it everything relevant to the grander picture.

JKK: That’s a good point.

CC: You know, you just have to look at what’s going on and assess it accordingly. Is it fun? Is it good? Do I want to come back and see what happens next?

JKK: So, in regards to that, what about the importance to overall continuity in comics. Because you’re talking about a character like Nightcrawler in, um, relation to all the other X-Men titles out there who are off on, you know, the Guardians of the Galaxy adventures, The Once and Future Juggernaut and all that. How do you reconcile Nightcrawler with all the other X-Men adventures in terms of establishing the value of the character in regards to different continuities?

CC: Yeah well, that’s the editor’s job, in terms of either providing sufficient information to the different creative talents working with him to either integrate the stories or the concept into the uber plot. I mean, if it were up to me, and it wasn’t, I would have … the death of Wolverine for me came too quickly after the resurrection of Kurt.

JKK: Yes … I totally agree with that.

CC: But because you know that creates the obvious conundrum, especially when you run down the list of characters of X-Men: Peter came back, and Kitty came back and Jean came back – at least twice. Rogue has come back and um, Wolverine came back at least twice. And Kurt just came back so why is this death any different from any other deaths? Then the obvious solution is well, come up with an answer. Come up with a resolution that resolves the question and leads to better stories. But that’s not the way it works. As a writer you have to find the best way to tell the story. In our case, it was to take Issue #7 and use it to show Nightcrawler reacting to the death of Logan, and that obviously became an element to use in the last five issues, up to and including whatever figures Kurt thought he saw in the after-life. But that’s just the way it is. Nothing integrates seamlessly … you do your best to make it enjoyable and if there is a problem, ideally that’s where you depend on the editor to give you a heads up and try to work it out and move on from there.

JKK: If you had complete editorial control, what would Chris Claremont’s Grand Unified Theory on the X-Men be?

CC: Totally different. You might as well ask what if Brian was the Grand Poo-Bah, or if Archie were the Grand Poo-Bah, if Stan were the Grand Poo-Bah – to answer that question, to paraphrase Shakespeare: that way lies madness.

JKK: It’s a big question.

CC: No, no, once upon a time, I – you know, could have sat for two hours and told you chapter and verse this is where it’s going, that is what it’s doing, and this is why it’s doing that … um, you kind of saw a sense of it in the seventeen issue of X-Men Forever that we got away with?

JKK: Yes, that’s right.

CC: Umm … the fact is that there is no real sense for me or for anyone, like Stan to say “Well, I woulda done this”, you know? The problem is: I’m not going to be the Grand Poo-Bah; Stan’s not going to be the Grand Poo-Bah, and if even if we were, and I wanted to impose my will on the X-Men – which I tried to do back in 2000, and then I was like editorial director, so I figured I could get away with it. And I had Bob’s “blessing” – it still created a shit-storm! Because when I sit back and say “well, Kitty is sixteen and wait a minute! She’s been shagging Pete Wisdom for fifty issues! So you’re saying that my … issues are invalid? And deep down in my heart and soul, I’m saying: You betcha!” That Pete Wisdom’s a naughty person!

JKK: Well, for me, Chris Claremont was – is the X-Men.

CC: Yeah, well, and for me, much as I appreciate it, umm, I suspect you would get vehement, impassioned and in my mind, absolutely justified counter-arguments from Joe and from Axel; because that’s the reality of the business. I mean, that’s like saying Superman is Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s. Well, it is, and it isn’t.

JKK: It must be hard to distance yourself from characters that you’ve invested so much of yourself in.

CC: Well, welcome to real life.

JKK: Last question: what’s the best work you’ve ever written?

CC: (Pauses) The one I haven’t written yet.

At this point, I had to reluctantly end the call. I spoke with Chris for about 75 minutes and while I had taken up so much of his time, I got the sense that he could have kept talking. Despite the fact that his twin boys were on their way home from school, anticipating their dad to make them supper, Chris had more to say.

An hour and a bit just didn’t cut it. Still, for what I received, I was truly grateful. It’s not often that you get given a comic legend’s phone number and told you could give him a call. It was a bit overwhelming.

But what could you expect? Claremont has had such a prolific writing history, that there is certainly more that this guy could tell me about the X-Men, about John Bolton or about an untold list of comic creators that this guy had interacted with in his amazing career span. To go back and punish myself with the questions I could have asked …well, like Claremont – and the Bard said: that way lies madness.

However, I can’t help but wonder what the best work he hasn’t written yet will be like.